Marawi buildings – with

a price tag of P10B – are ready but empty

The

Sarimanok Sports Complex, which faces Lake Lanao, has a seating

capacity of 3,700. (photo by Bobby Lagsa) |

Marawi homes remain in

disrepair as P10-B is poured into the construction of government

buildings. Displaced residents are now pinning their hopes on the

newly constituted Marawi Compensation Board. But big challenges lie

ahead.

By CARMELA FONBUENA

Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

March 2, 2023

The

bridges and the roads in Marawi City are sparkling and brand new,

but close to six years since followers of jihadist group Islamic

State laid siege to its city center, it’s still the sight of

abandoned and bombed out homes that immediately welcome visitors of

the former ground zero.

Past the Mapandi Bridge, which separated the safe zone and the

battle area in 2017, the pink walls of a newly painted commercial

building stood tall amid ruins. Nearby, a repaired house was painted

a neutral gray. They were few and far between.

The former site of battles is now called MAA or the “most affected

areas.” Life stood still here unlike the rest of Marawi City, called

the least affected areas or LAA, where residents returned and

rebuilt after the siege and new hotels have risen as well as coffee

shops that cater to visiting donors and development agencies.

There was a heavy downpour when the Philippine Center for

Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) visited the MAA in late January. The

first villages upon entry showed the presence of some residents, and

a few tricycles and private vehicles drove by. The humming sound of

electric saw and hammers hitting nails could be heard here and

there.

But deeper into the MAA, there was hardly no one. There were new

gates, but no work was done on the rest of the property.

Most

Marawi houses remain in disrepair. (photo by Carmela Fonbuena) |

Homes in these areas survived military air strikes during the

battles. The government wanted to demolish many of them at the start

of the rehabilitation work, citing safety considerations, but

residents protested. The large graffiti of the names and mobile

numbers of owners on walls pockmarked by bullets and bombs are

declarations of ownership, an assertion of their right to decide

what they would do with the property. A few cases of illegal

demolition are pending in courts against Task Force Bangon Marawi (TFBM),

the agency in charge of rehabilitation.

Time has doomed the abandoned Marawi homes to decay. But not the

government buildings. They were bright and shiny. New barangay

complexes, which cost almost P14 million each, have been completed

as well as village mosques and some school buildings. The police,

jail, and fire stations were almost done.

Electricity lines were in place. There was no power yet but the MAA

is expected to be connected soon. There were sun-powered light

posts, too. It’s the water source that is problematic.

|

The

big-ticket infrastructure projects are in sector 8 and 9 of the

MAA. Government funds did not cover the rehabilitation of

private properties. (photo by Bobby Lagsa) |

A total of P10.2 billion was released for the rehabilitation through

the years. The big-ticket infrastructure projects could be seen past

the rows of derelict homes, where modern public infrastructure was

built by the banks of scenic Lake Lanao. Many buildings were ready,

but without the residents, they were empty.

Samira Gutoc, an NGO leader, said the residents’ return to their

properties should have been the priority. She has been fighting for

residents’ right to return “without conditions.”

“Each house is crying for help. Naging secondary na ang bringing

back people. Di ba ‘right to return’ naman ang battlecry (Bringing

back people became secondary. Isn’t the battlecry ‘right to

return’)?” Gutoc said.

Not even 1% of MAA residents have returned

Only 100 families have been permitted to return to the MAA after

some repairs or reconstruction, based on data from TFBM, although

residents claimed a few families have returned without government

approval. It is not even one percent of over 17,793 households

displaced at the MAA during the siege.

A total of 953 families were resettled in permanent shelters and

4,916 others are still in transitory shelters elsewhere. The rest

have found temporary homes elsewhere.

Residents

visit their homes in the former battle area.

(photo by Bobby Lagsa) |

PCIJ chanced upon Rashmina Macabago, 57, at her family compound in

Brgy. Kapantaran. They secured a building permit before the pandemic

hit in 2020, but they did not have the funds to repair the property.

She and a few family members arrived with some construction

materials to reinforce a post that was already tilting. They hoped

to avert any further damage to the structure.

“Pera ang problema. Naghihintay kami sa ipamimigay. Wala pa rin (We

don’t have the money. We are waiting for what they will give us.

There’s none yet),” said Macabago.

Drieza Lininding, chairman of Marawi civil society organization Moro

Consensus Group NGO, said many residents cannot afford the

requirements to secure building permits, and not all who have

permits already have the money to buy construction materials. Many

others now live far away and cannot afford to return, he said.

The Marawi City local government unit (LGU) has so far only received

2,947 applications or 16.6% of households in MAA. Even for those who

could manage to afford processing building permits, Lininding said

there were fears that residents who have repaired their homes will

no longer be eligible for compensation. They will need the assurance

that it’s not true.

P10-B poured into government infra

The accomplishments of the

rehabilitation can be seen at the banks of Lake Lanao, the heart of

Marawi’s former city center which saw the fiercest battles and where the

siege leaders were killed. All but a few old structures were demolished

to make way for new buildings. It’s a reclamation area that the city

government said is government property, but which residents are

contesting.

The

Marawi Sports Complex has basketball courts, a running track,

and a football field. (photo by Bobby Lagsa) |

The new Sarimanok Sports

Complex can seat 3,700 spectators. The running track was newly painted

and goal posts were already placed at the football field. It can host

games for the youth not just in Marawi and Lanao Del Sur province but

all over the country. Marawi Mayor Majul Gandamra’s smiling photo

appeared in a banner on a makeshift stage, hung during his enthronement

and coronation as sultan, a traditional leader. Events like this

occasionally bring residents back to the MAA, but they leave as soon as

the activities are done.

Adjacent to the sports complex

is a one-hectare convention center that can host indoor events such as

weddings of Marawi’s rich and powerful. Inside, there’s an auditorium

with 1,000 seating capacity. Workers were already installing seats. An

engineer introduced himself to PCIJ to say that visitors were not

allowed yet, but the TFBM staff sorted it out immediately.

The white and green minaret of

Bato Mosque, where the militants holed up with their hostages for

months, now stands beside the newly built Marawi museum. Bato mosque

itself has been reconstructed and has taken a modern look. The Grand

Mosque, too, has been repaired and has changed its color from green to

gold.

The rehabilitation work was

divided into 22 projects, out of which 17 were completed or almost

completed as of December 2022, according to TFBM’s December 2022 report.

The rest of the projects are to be completed by December 2023, the

report said.

More than half or 56% of the

funds went to the National Housing Authority (NHA). It cost the agency

P2.3 billion to clear bombs and debris and P3.17 billion to construct a

road infrastructure, which has an underground facility.

|

Bato

Mosque (front) was reconstructed to take on a modern look while

the grand mosque was repaired and repainted. Both mosques became

strongholds of the militants during the siege.

(photo by Bobby Lagsa) |

The Marawi City LGU received

almost P2 billion or 19% of the funds for the construction of projects

such as the Grand Padian Central Market (P443.25 million), the Peace

Memorial Park (P312 million), the Lake Lanao Promenade (P380 million),

and 24 barangay halls.

The Local Water Utilities

Administration (LWUA) was allocated about P1 billion for the

construction of a Bulk Water System and Sewerage Treatment Plant, but

the agency has yet to begin its work. TFBM Field Office Manager Felix

Castro Jr. said they are expecting quicker action from the new head of

the agency.

Marawi Compensation Board

Residents are now pinning

their hopes on President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. to fulfill the failed

promise of his predecessor. Marcos finally appointed the members of the

Marawi Compensation Board (MCB), a body created under Republic Act 11696

to provide compensation for the loss or destruction of properties and

loss of lives as a result of the 2017 Marawi siege.

Lawyer Maisara Dandamun Latiph,

the newly appointed MCB chairman, told PCIJ the board will fast-track

its processes. She said they are planning to conduct consultations in

the next two to three months in order to finish the implementing rules

and regulations (IRR) of the law.

The board aims to formally

begin accepting claims by May or before the siege marks its sixth year.

She recognized that big

challenges lie ahead. “We are expected to deliver our mandate to pay the

monetary compensation for the personal properties as well as

[compensation to the families] of [those who are] legally presumed dead

and missing persons. We will also recommend interventions for further

recovery and rehabilitation,” Latiph told PCIJ.

The board has an initial

budget of P1 billion for the compensation of siege victims. The maximum

amount claimants may receive is yet to be determined, she said.

Latiph, who once belonged to

the NGO community, has the support of civil society organizations. They

are counting on her to champion their causes.

Bean There, Done

That: Exporting to the European Union

|

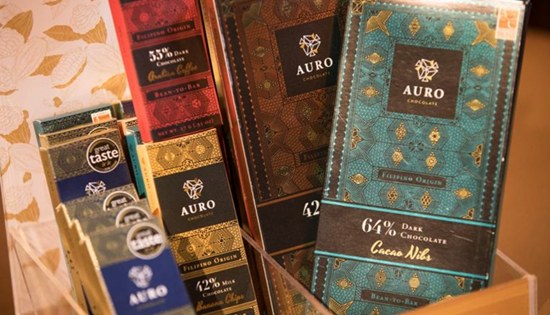

AURO

chocolates, a Filipino company, is one of currently, only 24

companies in the country who are able to export products to the

European Union tariff-free under the EU’s Generalized System of

Preferences Plus (GSP+). |

Philippine chocolate firm

exports to the EU

By

DTI-KMIS Information

and Creative Service Division

January 16, 2023

New beginnings

It was in 2013, while finishing her university degree in Chicago,

that Kelly Go got a taste of an American craft chocolate using

Philippine-origin cacao.

From this point, her career aspirations became clearer. After

graduation, she decided to learn more about this craft by enrolling

in Le Cordon Bleu in Paris for a Diploma in Culinary Arts. This

training further enhanced her knowledge and skills about the food

business.

The love for food, culture, and chocolate directed her destiny in

Germany where she deepened her expertise in industrial chocolate

production.

“We saw the potential of elevating the fine chocolate market in the

Philippines and an opportunity to pursue our shared dream to move

back home and contribute,” Kelly shared.

Responsible production

Their company, Auro Chocolate, was eventually launched in 2017 as a

tree-to-bar chocolate brand and social enterprise introducing

community development programs and premiums above commodity price

for supporting farmers.

|

Kelly

Go, co-founder and manager of AURO Chocolate, talks with

operators of the grinding machine at the AURO chocolate

plant in Calamba, Laguna, in the Philippines. AURO Chocolate

benefitted from the EU’s GSP+ programme which facilitates

the entry of certain products tariff- free into Europe. |

With all beans directly sourced, Auro is promoting sustainability by

working directly with local farmers to cultivating fine cacao beans,

improving ingredients, and expanding retail products with unique and

bold tropical flavours, such as dried mango.

From a team of 20 staff, it has grown to over 100 employees working

towards the export of its products to the European Union (EU) and

other countries since 2018.

We involve ourselves in every step of the process by consistently

working with our partner farmers to enable them to produce fine

quality cacao beans that meet international quality standards,”

Kelly added.

Breakthrough

There were challenges to be hurdled before successful exports to EU

could materialize.

“At selling events, people would question the quality of our

products as chocolates from the Philippines are unheard of,” Kelly

said.

To win the trust of consumers regarding chocolate products grown and

made in the Philippines, Kelly must be abreast of mandatory

procedural requirements.

The Philippine Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) – Export

Marketing Bureau (EMB) assisted Auro in completing the mandatory

regulatory requirements for exporting in EU. The Centre for

International Trade Expositions and Missions (CITEM) further

supported the company in organizing country booths in key

international trade fairs such as Salon du Chocolat in France.

The initiatives worked wonders for generating interest in Auro’s

fine cacao.

A plus for the business: GSP+

Sales have increased by almost 200% since the Covid pandemic. Auro

is directly exporting to more than 15 countries with over 40

European chocolate makers using the company’s fine cacao beans to

make Philippine-origin chocolate.

Kelly was delighted to learn that chocolatiers in the EU countries

were using her company’s chocolate products. Being able to export to

the EU means that Philippine cacao can compete globally with other

well-known chocolate brands.

The EU’s Generalized Scheme of Preferences (GSP+) removes import

duties from products coming into the EU market from developing

countries, thus, Kelly was able to competitively price her products

vis-à-vis other brands.

“Our chocolate bars are doing well due to GSP+, which serves as a

gateway support to the EU market,” Kelly added.

Kelly is proud of her products being able to stand side-by-side with

other internationally known brands, allowing her company to continue

to grow business with their EU partners.

Gaining together

The resultant increase in sales has benefited Kelly, together with

those who work for her company.

“Thanks to the GSP+ status, we have become part of the international

cacao beans market, which led to an increase in our sales. This

means there is a growing demand for our partner farming community’s

beans, thus generating more income for them, while providing a

stable market for their cacao.”

Moving Forward

Auro chocolates is ready to set higher standards of achievement

under Kelly’s leadership:

“We have exciting plans. On the farm side, we are to launch more

community initiatives that are interwoven with our current cacao

program. We are also expanding our sourcing to introduce new,

exciting origins of chocolates. Shifting to more environmentally

friendly practices and materials across the supply chain is also on

the cards.”

She leaves an inspiring message for aspiring exporters from the

Philippines: “Do not feel intimidated when trying to apply for GSP+.

DTI is there to assist you throughout the application and help make

your brand marketable. It’s also a great opportunity for your

products to be introduced and grow in the EU Market.”

Detained mother

reunites with daughter after 30 years

|

Anne

reunites with her daughter Jennifer at the Correctional

Institution for Women (CIW) in Mandaluyong City, Philippines.

(Photo by CIW) |

By

ICRC

October 20, 2022

MANILA – "Nasaan

ang anak ko? (Where is my daughter),” asked Anne* looking straight

at Jennifer*, who was introduced to her by a staff of the

International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). Smiling,

36-year-old Jennifer pointed to herself. They had last seen each

other over 30 years ago. Continuing to look at the younger woman

with some disbelief, Anne recalled that her daughter had a birthmark

somewhere around the nape of her neck. As she spotted it on

Jennifer, they were both overcome with emotions and embraced

tightly.

Jennifer was only six

years old when Anne was offered a job as a saleslady in Malaysia.

Like many Filipinos in search of a better life, she accepted it. “I

did not tell my mother that I wanted to work abroad because she

would have refused to let me go. So, I just left without a trace. I

was sure I would come back and my family would understand me because

I did it for them,” said Anne.

But the job in Malaysia

turned out to be a scam. Anne was tricked into becoming an

entertainer with a measly salary. When she was released from that

job, Anne became a domestic help and then toiled as a construction

worker.

After her contract ended,

Anne returned to the Philippines in 2006. However, she did not go

back to her family because she was afraid to see her mother. “I

thought she would reproach me for what I had done. I convinced

myself to pretend as if I were dead to my family,” she said, adding

that she chose to settle in another village in Mindanao and started

a farm.

Detained in the

Philippines

In 2017, Anne was arrested

in relation to armed conflict. The ICRC visited her at Taguig City

Jail a few months after her arrest as part of its humanitarian

mandate and activities in the Philippines. “We have been helping

detainees all over the world for more than 150 years, focusing on

people deprived of their liberty in relation to armed conflicts and

other violence. We look into how detainees are treated during their

arrest and detention and monitor their health and living conditions.

We also help to restore and maintain communication between detainees

and their family members,” explained Alvin Loyola, the ICRC staff

who accompanied Jennifer to meet Anne.

Anne learned about the

ICRC’s Family Visit Programme (FVP), under the Restoring Family

Links (RFL) initiative, to help detainees separated from their loved

ones because of armed conflicts. The RFL initiative involves tracing

detainees’ family members, re-establishing and maintaining contact,

reuniting families and seeking to clarify the fate and whereabouts

of those who remain missing. Through the FVP, families of detainees

can travel from their hometowns to visit their detained loved ones.

“It is very important because it allows detainees to re-establish or

maintain contact with their families and improves their

psychological well-being,” said Mariegen Balo, ICRC staff.

Anne also desired to meet

her daughter when she found out her whereabouts through relatives.

But the programme was suspended in 2020 because of the COVID-19

global pandemic. When the travel restrictions were eased in 2022 and

family visits resumed, the ICRC scheduled Anne’s long-awaited

reunion with her daughter.

Together at last

In July, an ICRC team

accompanied Jennifer to visit her mother, who is now detained at the

Correctional Institution for Women (CIW) in Mandaluyong City. Anne

said she did not know how she would approach her daughter, whom she

had last seen three decades ago. “I wondered, should I ask for

forgiveness first, or do I just hug her?”

In July, an ICRC team

accompanied Jennifer to visit her mother, who is now detained at the

Correctional Institution for Women (CIW) in Mandaluyong City. Anne

said she did not know how she would approach her daughter, whom she

had last seen three decades ago. “I wondered, should I ask for

forgiveness first, or do I just hug her?”

But Jennifer, who had

managed to beat the odds and graduate from college with her

grandmother’s help, said her mother did not need to worry at all.

Even though they had not been in contact for 30 years, Jennifer said

she did not harbour any resentment against her mother. In fact,

every year on 30 January – Anne’s birthday – Jennifer would put a

post on social media in her honour. “The only photo I had of my

mother was destroyed in a flood so I used photos of my siblings and

me for the posts. I used to pray hard for the day that I would see

her again,” said Jennifer.

The mother and daughter’s

reunion happened just a few days after Jennifer’s 36th birthday, so

the ICRC team asked Anne about her wish for Jennifer. “I wish her

more happiness in life and that she may be given more

opportunities,” said Anne.

As part of the FVP, Anne’s

family will make two ICRC-supported visits every year to meet her.

Now that she has been reunited with Jennifer, Anne said she looks

forward to making up for lost time.

*Names have been changed to protect identity.

2021 Eastern Visayas poverty situation

22 in every 100

families in Eastern Visayas are poor

By

PSA-8

October 14, 2022

TACLOBAN CITY -

Poverty incidence among families in Eastern Visayas in 2021 was

estimated at 22.2 percent. This implies that in 2021, about 22 in

every 100 families in the region were poor or have income that were

below the poverty threshold, or the amount needed to buy their basic

food and non-food needs.

Among provinces, Eastern

Samar posted the highest poverty incidence in 2021 at 29.4 percent,

while Southern Leyte registered the lowest poverty incidence among

families at 16.0 percent. Eastern Samar and Samar registered higher

poverty incidences among families than the regional level in 2021,

while the rest of the provinces posted lower poverty incidences than

the regional estimate at 22.2 percent.

Significant improvements

in poverty incidence among families were noted in Eastern Samar and

Northern Samar. Poverty incidence among families in Eastern Samar

dropped to 29.4 percent in 2021 from 40.9 percent in 2018. The

province of Northern Samar, meanwhile, registered 19.3 percent

poverty incidence among families in 2021, lower than the 27.6

percent in 2018. On the other hand, poverty incidence among families

in Biliran significantly increased to 19.9 percent in 2021 from 13.7

percent in 2018. Samar registered 27.0 percent poverty incidence

among families in 2021, significantly higher than the 22.2 percent

in 2018 (Table 1).

Given the new master

sample, PSA was able to generate reliable statistics down to the

provincial level as well as for highly urbanized cities (HUCs).

Poverty incidence among families for Tacloban City, the lone HUC in

the region, was significantly higher in 2021 at 10.7 percent

compared with its recorded 5.3 percent poverty incidence among

families in 2018.

Around 29 out of 100

individuals in Eastern Visayas are poor

Poverty incidence among

population in Eastern Visayas in 2021 was estimated at 28.9 percent.

This implies that in 2021, around 29 in every 100 individuals in the

region belonged to the poor population whose income were not

sufficient to buy their minimum basic food and non-food needs.

Among provinces, Eastern

Samar posted the highest poverty incidence among population in 2021

at 37.7 percent, while Southern Leyte registered the lowest poverty

incidence among population at 21.5 percent. Eastern Samar, Samar,

and Leyte (excluding Tacloban City) registered higher poverty

incidences among population than the regional figure in 2021, while

the rest of the provinces posted lower poverty incidences than the

regional estimate at 28.9 percent.

Significant improvements

in poverty incidence among population between 2018 and 2021 were

noted in Eastern Samar and Northern Samar. Poverty incidence among

population in Eastern Samar dropped to 37.7 percent in 2021 from

49.5 percent in 2018. The province of Northern Samar, meanwhile,

registered 25.9 percent poverty incidence among population in 2021,

lower than the 34.3 percent in 2018. On the other hand, poverty

incidence among population in Biliran significantly increased to

27.2 percent in 2021 from 19.6 percent in 2018 (Table 2).

Further, poverty incidence

among population in Tacloban City in 2021 significantly increased to

15.6 percent from 8.1 percent in 2018.

Subsistence Incidence

among Families

The subsistence incidence

among families in Eastern Visayas in 2021 was estimated at 7.2

percent. This means that in 2021, about 7 in every 100 families in

the region have income below the food threshold or the amount needed

to buy their basic food needs and satisfy the nutritional

requirements set by the Food and Nutrition Research Institute (FNRI)

to ensure that one remains economically and socially productive.

Among provinces, Eastern

Samar posted the highest subsistence incidence among families in

2021 at 12.1 percent, while Northern Samar registered the lowest

subsistence incidence among families at 3.7 percent. Eastern Samar,

Samar, and Leyte (excluding Tacloban City) registered higher

subsistence incidences among families than the regional figure in

2021. The rest of the provinces posted lower subsistence incidences

than the regional estimate at 7.2 percent.

Significant improvements

in subsistence incidence among families between 2018 and 2021 were

noted in Eastern Samar and Northern Samar. Subsistence incidence

among families in Eastern Samar declined to 12.1 percent in 2021

from 16.5 percent in 2018. The province of Northern Samar,

meanwhile, registered 3.7 percent subsistence incidence among

families in 2021, lower than the 7.2 percent in 2018. On the other

hand, subsistence incidence among families in Biliran significantly

increased to 6.6 percent in 2021 from 2.2 percent in 2018 (Table 3).

In addition, subsistence

incidence among families in Tacloban City significantly increased to

2.1 percent in 2021 from 1.0 percent in 2018.

Subsistence Incidence

among Population

Subsistence incidence

among population in Eastern Visayas in 2021 was estimated at 10.4

percent. This translates that in 2021, about 10 in every 100

individuals in the region have income below the food threshold or

the minimum amount needed to buy their basic food needs.

Among provinces, Eastern

Samar posted the highest subsistence incidence among population in

2021 at 17.1 percent, while Northern Samar registered the lowest

subsistence incidence among population at 5.8 percent. Eastern Samar,

Samar, and Leyte (excluding Tacloban City) registered higher

subsistence incidences among population than the regional figure in

2021. The rest of the provinces posted lower subsistence incidences

than the regional estimate at 10.4 percent.

Significant improvements

in subsistence incidence among population between 2018 and 2021 were

noted in Eastern Samar and Northern Samar. Subsistence incidence

among population in Eastern Samar decreased to 17.1 percent in 2021

from 22.0 percent in 2018. The province of Northern Samar,

meanwhile, registered 5.8 percent subsistence incidence among

population in 2021, lower than the 10.6 percent in 2018. On the

other hand, subsistence incidence among population in Biliran

significantly increased to 10.1 percent in 2021 from 3.5 percent in

2018 (Table 4).

Subsistence incidence

among population in Tacloban City significantly increased to 3.3

percent in 2021 from 1.6 percent in 2018.

Food Threshold

In 2021, a family of five

(5) in Eastern Visayas needed at least P7,819 per month, to meet the

family’s basic food needs. This amount represents the average

monthly food threshold for a family of five (5). This figure is 6.5

percent higher compared with the 2018 level of P7,345.

Biliran posted the highest

food threshold among the provinces in Eastern Visayas with P8,471

average monthly food threshold for a family of five (5) in 2021. On

the other hand, Samar had the lowest average monthly food threshold

for a family of five (5) at P7,342 in the same year (Figure 5).

Increases in food

threshold between 2018 and 2021 were observed in all provinces,

except in Eastern Samar, which registered a -0.5 percent decrease in

food threshold. Biliran posted the biggest increase in food

threshold at 20.5 percent (Table 5).

Meanwhile, average monthly

food threshold for a family of five (5) in Tacloban City was

estimated at P8,075 in 2021. This registered an increase of 16.4

percent compared with its P6,940 level in 2018.

Poverty Threshold

The average monthly

poverty threshold for a family of five (5) in Eastern Visayas in

2021 was estimated at P11,187, an increase of 7.4 percent from its

2018 level of P10,411. This represents the amount needed every month

to meet the family’s basic food and non-food needs.

Among the provinces, the

highest average monthly poverty threshold for a family of five (5)

was observed in Eastern Samar at P12,052 in 2021. On the other hand,

Samar registered the lowest average monthly poverty threshold for a

family of five (5) at P10,525 in the same year (Figure 6).

Increases in poverty

threshold between 2018 and 2021 were observed in all provinces,

except in Eastern Samar, which registered a -0.5 percent decrease in

poverty threshold. Biliran posted the biggest increase in poverty

threshold at 16.8 percent.

Meanwhile, average monthly

poverty threshold for a family of five (5) in Tacloban City was

estimated at P11,564 in 2021. This registered an increase of 16.4

percent compared with its P9,935 level in 2018.

Clustering of Provinces

based on Poverty Incidence

All provinces in the

country were clustered from 1 to 5 using poverty incidence among

families as the clustering variable. Cluster 1 comprises the bottom

poor provinces and Cluster 5 comprises the least poor provinces.

In 2021, two (2) provinces

moved one (1) cluster lower from their cluster categories in 2018,

namely Biliran and Samar. Two (2) provinces, Northern Samar and

Southern Leyte, moved one (1) cluster higher from their cluster

categories in 2018. The rest of the provinces maintained their 2018

cluster categories.

Among the provinces, only

Southern Leyte was categorized as Cluster 4. Three (3) provinces,

namely: Biliran, Leyte (including Tacloban City), and Northern Samar

belonged to Cluster 3, while Eastern Samar and Samar were classified

in Cluster 2.

◄◄home

I

next►►